What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition that is characterized by gradual memory loss and cognitive decline. As AD progresses, our ability to carry out daily tasks becomes more difficult, worsening quality of life. Common symptoms associated with AD include disorientation, confusion, and difficulty swallowing, communicating, and walking. Such occurrences can cause an individual to feel frustrated if they cannot independently function and perceive a lack of control. As these symptoms worsen with age, feelings of agitation and fear can emerge as the person with AD slowly forgets their loved ones and places they once recognized. For that reason, people with AD may start to socially isolate themselves in an attempt to look for familiarity and feel less overwhelmed.

Alzheimer’s Disease Statistics

AD is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States. To put that into perspective, AD is considered more fatal than breast cancer, prostate cancer, and essential hypertension combined. AD is so common that it accounts for 60-80% of all dementia cases. In 2025, scientists estimated that 6.7-7.2 million Americans, aged 65 years or older, had AD. This number is expected to rise to 12.7-13 million by 2050. Despite how widespread AD is, the expenses to care for this condition are far from affordable. In 2022, it was estimated that the average lifetime medical care cost per person living with AD was $392,874, which far exceeded treatment plans for other deadly ailments (e.g., heart disease). Consequently, 11 million Americans report providing unpaid care to their loved one with AD. These uncompensated wages can cause a caretaker to experience burnout and negatively impact the care they provide for their loved one.

What further contributes to this issue is that AD disproportionately affects people who identify with marginalized backgrounds. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, older Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to develop AD compared to older White individuals. Additionally, women make up two-thirds of AD cases in the United States. These health disparities are influenced by social and structural barriers that hinder minority populations’ access to healthcare and educational opportunities. Such inequities harm patients’ quality and quantity of AD treatment and further contribute to their lack of trust in the medical field and poor lifestyle habits. Coupling these factors with the fact that there is presently no cure for AD underscores the importance of studying this disease.

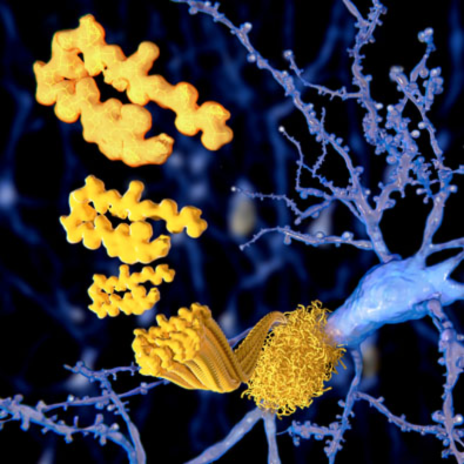

Amyloid Beta (Aβ) Plaques

One hallmark of AD is the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques around the brain. Aβ plaques are small fragment peptides that are derived from a larger protein called the amyloid precursor protein (APP). APP is normally present within the body’s tissues and organs, especially the brain and spinal cord. Although there is limited information about the role of APP, we currently know it is responsible for ensuring the movement, production, development, and maturation of neurons in regular circumstances. However, once enzymes break down APP into Aβ, these proteins accumulate around neurons and form plaques. This toxic buildup leads to apoptosis (i.e., cell death) in the surrounding neurons, causing the brain to lose its shape and become smaller. When neurons deteriorate, they are no longer able to communicate, produce energy, and repair themselves. In turn, cognitive decline and memory-deficit signs and symptoms of AD worsen over time as the brain loses its ability to clear out the plaques from forming and regenerating new neurons. Advanced aging will make this occurrence happen more frequently as the person’s AD progresses and they develop Aβ plaques.

Intervention Strategy: Anti-Amyloid Therapy

Due to the pervasiveness of Aβ plaques, new intervention strategies have emerged to mitigate the effects of these neurotoxins. One treatment researchers are currently investigating is anti-amyloid therapy. Anti-amyloids are a form of drug immunotherapy, meaning they have antibody properties that target Aβ plaques. More specifically, anti-amyloids serve as monoclonal antibodies, meaning they are laboratory-produced proteins that imitate the body’s natural antibodies. Once the plaques are surrounded by monoclonal antibodies, the brain’s immune cells engulf and destroy these neurotoxins.

The three current FDA-approved anti-amyloid drug therapies are lecanemab-irmb (Leqembi), donanemab (Kisunla), and aducanumab (Aduhelm). Leqembi was approved by the FDA in January 2023, while Kisunla was approved in July 2024. Aduhelm was speedily approved by the FDA in 2021 but was discontinued in 2024. Unlike Leqembi and Kisunla, Aduhelm only extracts Aβ plaques without positively influencing the cognitive decline symptoms associated with AD. For that reason, the manufacturers of Aduhelm have until 2030 to prove that the drug can satisfy both requirements before it is permanently removed from the market.

Leqembi and Kisunla are primarily designed for patients who have early AD or mild dementia and are administered via intravenous (IV) infusion in the vein at a low dose. Over time, the dosages increase until they reach the desired amount prescribed by a clinician. Leqembi is given out every two weeks, whereas Kisunla is injected every four. It is important to note that these drug therapies are not intended to be used to cure AD; instead, they reveal promising results towards reducing the progression of cognitive decline by clearing out Aβ plaques in the illness’s beginning stages.

Anti-Amyloid Therapy Disadvantages

Even though anti-amyloid therapies do propose strong results, there are some drawbacks patients should be aware of. For one, anti-amyloid therapies are expensive and are only covered by Medicare and private health insurance programs. Medicare solely provides coverage benefits for patients enrolled in a clinical trial, which can be difficult to enter due to strict eligibility requirements. For example, being able to participate in Aduhelm clinical trials is quite limited, as patients who take blood thinners, other than aspirin, or who have a history of heart disease, stroke, bleeding problems, or kidney or liver disorders are disqualified. These criteria exclude 90% of people covered by Medicare from being able to be a part of the study and having their anti-amyloid prescriptions paid for. As a result, these people may not be able to benefit from the positive effects anti-amyloid therapies can provide. Simply put, rather than having immediate access, patients may need to wait until new research and studies offer new medications that they can afford and are eligible for.

Another downside of anti-amyloid therapies are their potential side effects, including amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). ARIA involves symptoms like brain swelling and bleeding, dizziness, headaches, nausea, vision problems, diarrhea, allergic reactions, confusion, and falls. However, these complications are often asymptomatic, meaning clinicians can only truly discern if their patient is experiencing ARIA through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. This shows that anti-amyloid therapies are not one-size-fits-all and are much more complex. If you are considering anti-amyloid therapy or participating in a clinical trial, it is best that you first consult with your physician to get their feedback on how your body would react to the drug and if it is suitable for you. This is especially true as anti-amyloid therapies are not effective for severe cases of AD, meaning only people who caught their AD in its early stages will benefit from this drug. The number of people who are able to do this, though, are few and far between, as the average age of diagnosis for AD is between 75 and 84 years of age. That leaves a 10-year gap of potentially being undiagnosed, as the typical age for late-onset AD is 65 years old. At that rate, there is an increased chance of AD symptoms worsening, which can make anti-amyloid therapies futile treatments. This is particularly crucial to consider, as anti-amyloid therapies cannot reverse any of the symptoms and outcomes AD brings to the patient before the medication is introduced.

Future Directions

Despite its shortcomings, the production of anti-amyloid therapy is quite monumental, as such medications could be prescribed to patients with AD who are still in the early stages of their disease. This is important to note because it could mean a decrease over time in the number of people who are experiencing severe AD. In order to reach that point, we need to conduct more research and clinical trials to produce newer anti-amyloid therapies that could be made available to the general public at potentially lower costs. We are already seeing the inception of anti-amyloid therapies into neuropsychology practices via pre-treatment testing. Such assessments can allow us to diagnose AD at early ages and prevent it from advancing to extreme conditions. If more research and positive outcomes are generated from these drugs, a vaccine against Aβ could be the next step. In addition, because anti-amyloid therapies are not universally available, other countries should be encouraged to perform research and clinical trials on these drugs as well. This form of global research collaboration would allow us to produce more inclusive, diverse, and faster results that could benefit patients diagnosed with AD and their loved ones.

Being prescribed anti-amyloid drugs could lead to both patients and caretakers having better qualities of life, which could make it easier to provide care and comfort for one another. Caretakers could benefit from these drugs, by reducing burnout levels for those caring for their loved ones. This is because the person with AD could have more chances to act independently and remember important information, thus reducing their feelings of frustration and a lack of autonomy. Furthermore, patients’ social lives could improve as they feel more comfortable and ready to make personal connections with others, especially if their ability to communicate and their cognition are not drastically impaired. Overall, such benefits highlight the significance of these drugs, while the drawbacks remind us how much work remains before we can truly understand AD and its interventions.

Sources:

- What is Alzheimer’s Disease? Symptoms & Causes | alz.org

- Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Statistics

- Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures

- Culture, Ethnicity, and Level of Education in Alzheimer’s Disease – PMC

- Amyloid Precursor Protein – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

- APP gene: MedlinePlus Genetics

- Donanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s | alz.org

- What to know about the new Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi

- Anti-Amyloid Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease

- Amyloid-related Imaging Abnormalities in Alzheimer Disease Treated with Anti–Amyloid-β Therapy | RadioGraphics

- What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease? | National Institute on Aging

- How Age and Other Demographics Affect Alzheimer’s and Dementia Risk